Yesterday, HaggardHawks tweeted this fairly peculiar definition:

As a verb, the girl’s name REBECCA can be used to mean ‘to destroy a gate’.

— HaggardHawks Words (@HaggardHawks) July 30, 2015

In fact, Rebecca is just one of a handful of first names that you can use as a word in its own right. A George, for instance, is a loaf of brown bread. Abigail is an old nickname for a lady’s maid. A Robert is a restaurant waiter (inspired by a series of cartoons from the late 1800s). Peter can be used as a verb to mean “to blow open a safe” (because St Peter held the keys to Heaven). And as for John—well, he can be a nickname for anything from your signature (thanks to John Q Hancock) to the client of a prostitute.

But what’s the story behind Rebecca? Well, if you know your British history—and a hat-tip to @Evansianl, who got it spot on—you’re probably way ahead of us:

@HaggardHawks no doubt fron the Rebecca Riots in Wales!

— Edward Evans (@EvansianI) July 30, 2015

The Rebecca Riots were a series of disturbances in the early 1840s prompted by the increasing exploitation and worsening prospects of the local farming communities in Wales. In the years leading up to the riots, farmers had had to contend with several seasons of bad weather and failed crops, poor financial returns on their produce, increased rents from landowners, and the on-going enclosure of common land. On top of that, farmers (who were already paying 10% of their profits to the local church) were then faced with the newly-amended Poor Law Act of 1834, which increased taxes and began channelling more and more public money into the controversial workhouse system.

Enough was understandably enough. And in southern Wales, local farmers began taking their frustration out on what they saw as the embodiment of all their woes: the local tollgates.

Enough was understandably enough. And in southern Wales, local farmers began taking their frustration out on what they saw as the embodiment of all their woes: the local tollgates.

|

| “Down with this sort of thing.” |

By the early nineteenth century, there were already 30,000 miles of toll roads and 8,000 toll gates in Britain, each of which was overseen by a local body of landowners and businessmen called a turnpike trust. On paper, the idea was simple enough—the money the toll roads raised would go towards the upkeep and repair of the roads themselves. But in practice, it often proved hopelessly flawed.

The turnpike trusts were left largely to their own devices; they could charge however much they wanted, and could introduce however many tollgates on their land as they wished. Before long, many were taking full advantage of the loopholes in the system: by the 1830s, Carmarthen in south Wales was completely encircled by tollgates, leaving no free route into or out of the town. The gates, it seemed, had to go.

On 13 May 1839, an angry crowd rallied together and destroyed the tollgate in the tiny hamlet of Efailwen, 20 miles west of Carmarthan. This initial protest quickly sparked others, and soon tollgates all across south Wales were being attacked and destroyed by groups of locals fed up with the extortionate prices they were being forced to pay. The protests rumbled on for several months, reaching a peak in 1842 when a combination of an unexpectedly successful harvest and a cut in the taxes imposed on imported meat led to the prices of corn and cattle collapsing.

Within a year, however, it was all over. As the protests had grown ever more violent (a young woman working at a tollgate in Hendy, near Llanelli, was shot and killed in 1843), a diplomatic solution was quickly sought, and the Turnpikes Act of 1844 slashed the toll rates, and amalgamated all the turnpike trusts into one regulated body.

That’s all well and good, of course, but one question remains: why “Rebecca”?

Well, to answer that we need to turn to the Bible. Rebecca was the name of Isaac’s wife, and in the Book of Genesis we’re told that before leaving her family home to go and marry him, Rebecca’s mother gave her a blessing:

And they blessed Rebekah, and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them.

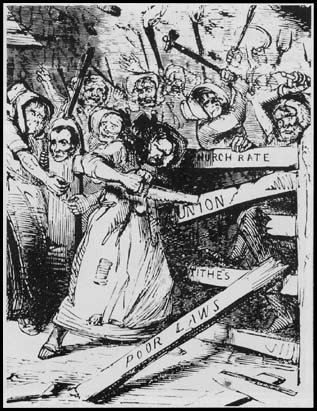

Clearly, it was the words “let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them” that gave the Rebecca Riots their name—and inspired the protesters in more ways than one: if you noticed that some of the befrocked protestors shown in the picture above looked, well, less than ladylike, that’s because they quite literally are.

As the protests picked up pace across south Wales, any gate-destroying farmers not wanting to be identified began disguising themselves in women’s clothing. These “Rebeccas” soon became the figureheads of the “Rebecca Riots”, with the leader of each protest even taking on the role of “Rebecca” in a bizarre role play before each gate was destroyed.

As the protests picked up pace across south Wales, any gate-destroying farmers not wanting to be identified began disguising themselves in women’s clothing. These “Rebeccas” soon became the figureheads of the “Rebecca Riots”, with the leader of each protest even taking on the role of “Rebecca” in a bizarre role play before each gate was destroyed.

As strange as all that might sound, it’s worth bearing in mind that the Rebecca Riots grew out of genuine hardship and sense of frustration, and led to a change in the law that, although not perfect, nevertheless improved conditions for hundreds of the poorest people involved. Today, they are quite rightly seen as one of the most important movements in British social history.